Housing Inequality and Justice

Toward Equitable Housing as a Human Right in the U.S.

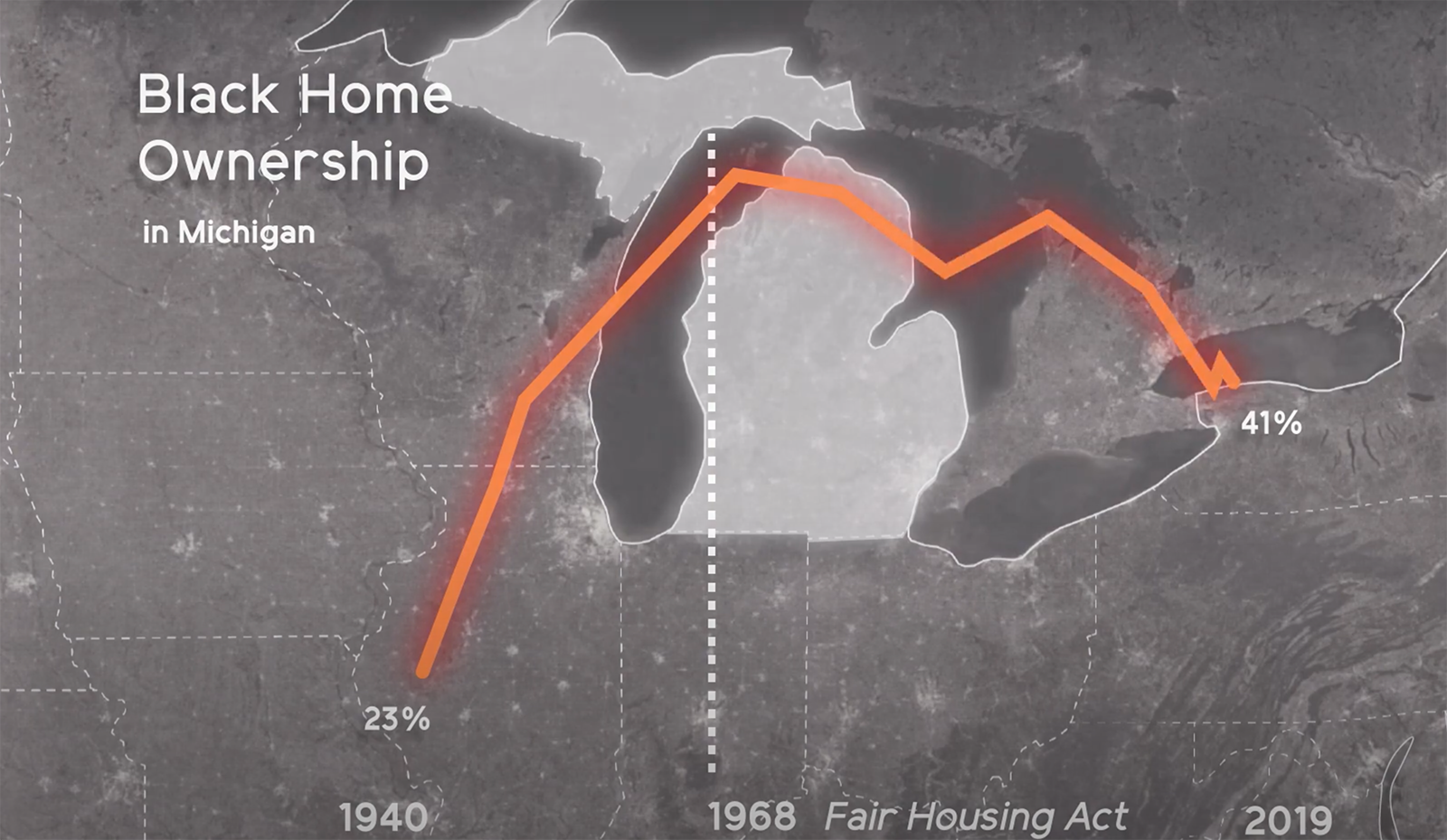

Focusing on Detroit, CID Founding Director and Associate Research Professor at the Institute for Social Research Fabian Pfeffer and Professor and Associate Dean for Research and Creative Practice at Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning Kathy Velikov draw on the city’s history before and after the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited the legal and systematic discrimination of racist lending policies, land covenants, high rents, and instruments such as redlining, where people of color were refused home loans because they were deemed a poor financial risk.

“On a street by street, block by block scale, owning real estate has enabled families to accumulate and pass down wealth through generations,” Velikov explains in the video.

Resources

In 1968, the average black family’s wealth was $6,674 compared to the average white family’s wealth at $70,786. In 2019, the average black family’s wealth had only risen to $17,409. Interestingly, the average wealth for both black and white families was nearly 2.5 times over the 51-year time period.

Wealth accumulation over time has expanded beyond the simple everyday household to include businesses, trusts, funds, and family offices. These mechanisms for translating “family money” into “family wealth” have involved real estate that focuses on urban renewal and gentrification, as it fuels predatory rental markets, neglected housing developments, eviction threats, displacement, and instability in low-income, predominantly black and brown neighborhoods in most U.S. cities.

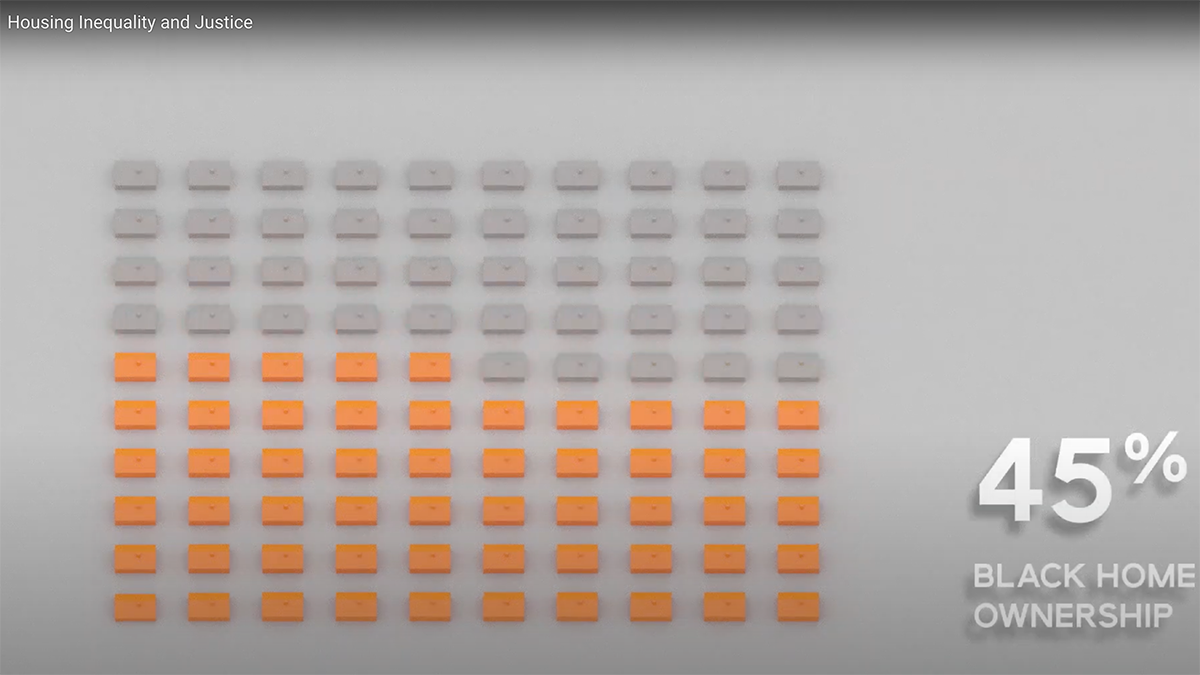

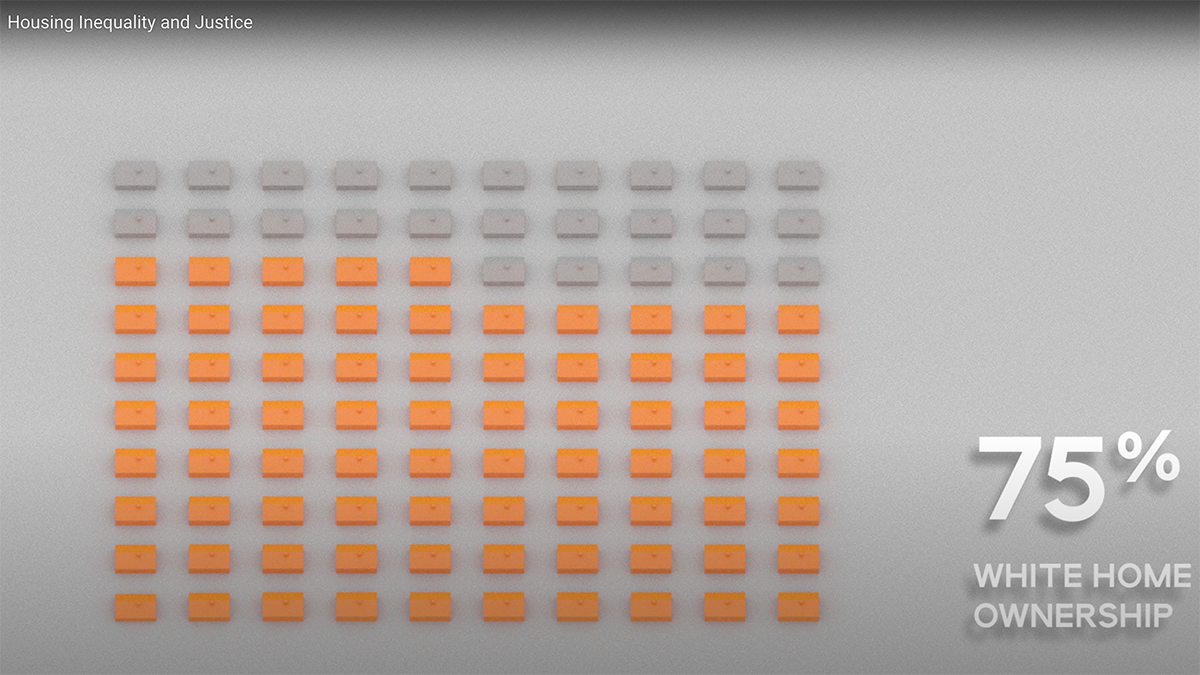

The first half of the video breaks down how historic discrimination and dispossession are the main reasons behind the racial wealth gap and housing disparity in the United States. This housing inequality persists today. Nationally only 44% of Black Americans own homes compared to about 74% of White, Non-Hispanic Americans.

“Wealth is a critical safety net for families that protects against unexpected financial storms. For the American middle class, home equity accounts for about two thirds of their wealth. But home ownership is not evenly distributed, particularly by race.”

Researchers Kathy Velikov and Fabian Pfeffer state, “Housing inequality cannot be addressed with a one size fits all solution because every street, neighborhood, district, county and city are different.” What works for a neighborhood in Detroit does not necessarily work for neighborhoods in Chicago, Atlanta, or Los Angeles.

The second half of the video shows how gaps in home ownership and wealth can be diminished. Drawing on experts and community voices from Detroit, the video introduces a variety of solutions.

Explore the “real utopian” solutions for and Housing Inequality https://youtu.be/8iOEp3wf640

and Wealth Inequality https://youtu.be/PAHYCiiXQlQ.

To address housing inequality, multiple and ambitious interventions are necessary

- Restrict predatory real estate practices and evictions so that housing is protected as a right.

- Revise property tax codes to reduce the burden on low-income families through progressive strategies such as property tax rates that scale with level of income.

- Update zoning ordinances to allow for more mixed-use, midrise, and accessory dwellings in neighborhoods, as well as alternative ownership structures such as community land trusts and cooperatives.

- Increase economic security through universal basic income so everyone can have the financial capacity to buy and maintain a home and participate in the benefits of home equity, Americans’ primary source for wealth.

- Offer reparations that prioritize accessibility for the historic injustices to those who have been dispossessed of housing and real estate opportunities for decades.

- Empower communities through new structures and institutions through which communities can reclaim power, agency, self-determination, and dignity in shaping their neighborhoods to thrive.

“What is really important is that each option gets scaled as it fits the historical context and community-based need, which can thoroughly be addressed by establishing new governmental departments, neighborhood-based ownership structures and other alternatives,” they add. To make the ideas more accessible, the team drew on both social scientific and artistic work to visualize radical inequalities and communicate them in an accessible way.

About the Housing Inequality and Justice Project

CID Team Members

Fabian Pfeffer

Asher Dvir-Djerassi

Jasmine Simington

Taubman College Collaborators

Kathy Velikov

Tesas Broek

Minghui Li

Jordan Zauel

Sofia Hiltner